GALLSTONES

What is Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy?

Gall bladder removal (cholecystectomy) is a commonly performed surgical procedure for the treatment of gall bladder stones. Today, gall bladder surgery is performed laparoscopically i.e. using minimally invasive keyhole surgery. The medical name for this procedure is Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Removal of the gallbladder is not associated with any impairment of digestion in most people.

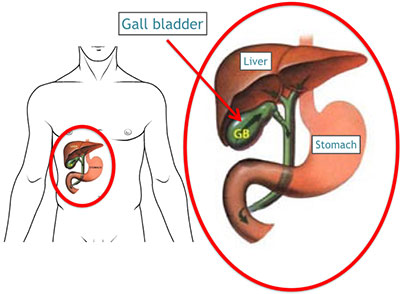

What is the Gall Bladder?

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ that rests beneath the right side of the liver. Its main purpose is to collect and concentrate a digestive liquid (bile) produced by the liver. Bile is released from the gallbladder after eating, aiding digestion. Bile travels through narrow tubular channels (bile ducts) into the small intestine.

What is gallstone disease?

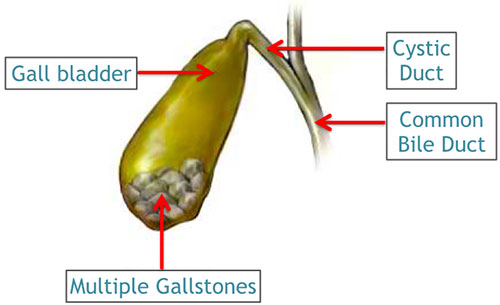

Gallstones are small hard masses consisting primarily of cholesterol and bile salts that form in the gallbladder or in the bile duct, causing several medical problems. It is uncertain why some people form gallstones. Gallstones are more common in women, older patients and ethnic groups and are associated with multiple pregnancies, obesity and rapid weight loss. There are no known means to prevent gallstones.

Stones tend to grow for the first 2-3 years, at which point growth tends to gall stone stabilize; 85 percent of all gallstones are less than 2cm in size. Most patients with gallstones remain symptom-free for many years and may, in fact, never develop symptoms. However, the consequences of gallstones may be severe.

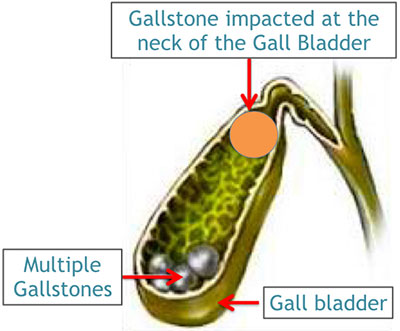

They may be associated with brief episodes of biliary pain (misnamed "colic"). These stones may block the flow of bile out of the gallbladder, causing it to swell and resulting in sharp abdominal pain, vomiting, indigestion and, occasionally, fever. The gall bladder may get inflamed (cholecystitis) which can be acute or chronic, form pus (empyema) and may even rupture (perforation of gall bladder), resulting in spillage of infected material into the abdominal cavity (peritonitis).

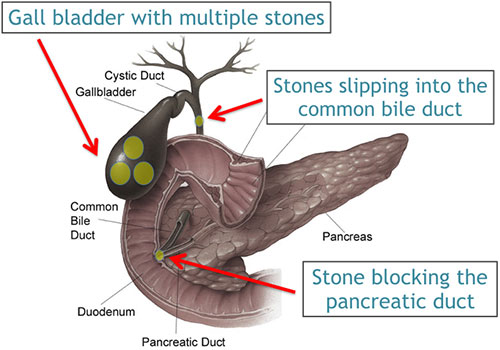

If the gallstone blocks the common bile duct, a yellowing of the skin (jaundice) can occur; this is sometimes associated with inflammation of the bile duct system (cholangitis). Small stones may block the duct of the pancreas, causing inflammation (pancreatitis), which is potentially fatal. It is rarely associated with gall bladder cancer.

How to diagnose gallstones?

Ultrasound is most commonly used to find gallstones. It is done after 6-8 hours of fasting. A sound-wave emitting probe is placed on the abdominal wall and reflected shadows of the various internal organs are seen on a television monitor.

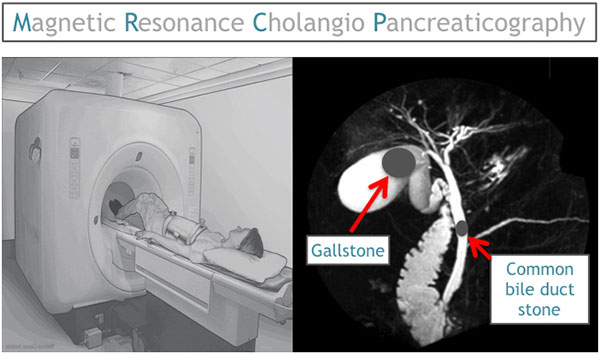

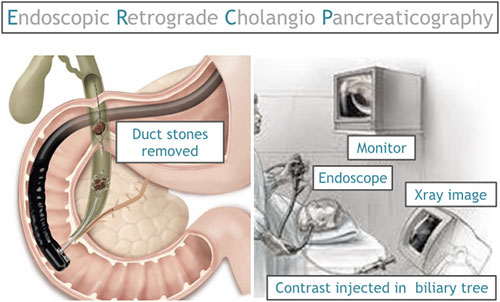

In a few more complex cases, other radiological tests (e.g MRCP, CT scan, ERCP, EUS) may be used to evaluate gallbladder disease.

MRCP (magnetic resonant cholangio-pancreaticography) relies on magnetic waves to take sharp images of the abdominal insides. This is usually advised when there is a strong suspicion of small stones slipping into the bile ducts and causing jaundice, pancreatitis etc. Like the ultrasound waves, these magnetic waves too do not cause ‘radiation’, are hence harmless.

ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreaticography) is done when there are documented bile duct stones, or a narrowing (stricture) of the lower bile duct, casuing obstruction to the bile emptying in the intestines. This involves passing an endoscope down the mouth, food pipe and past the stomach into the duodenum. Here, the small opening of the bile duct into the small intestine is visualized and cannulated with specialized instruments that can release any narrowing or extract any bile duct stones. This may also be used along with EUS (endoscopic ultrasound) when an MRCP is unavailable.

Blood tests are required to suggest complications like jaundice, infection and pancreatitis. These include a complete blood count, blood sugars, liver function tests, renal function tests, pancreatic enzymes etc.

What is the treatment for gallstones?

Gallstones do not go away on their own. Some can be temporarily managed with drugs or by making dietary adjustments, such as reducing fat intake. This treatment has a low, short-term success rate. Symptoms will eventually continue unless the gallbladder is removed. Surgical removal of the gallbladder is the time-honored and safest treatment of gallbladder disease. Asymptomatic patients usually develop symptoms before they develop complications. Therefore, with few exceptions, patients with asymptomatic gallstones can be observed with regular follow up.

Until two decades ago, the prevailing surgical treatment of symptomatic gallstones was an open operation through an abdominal incision to remove the gallbladder. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a minimally invasive surgical procedure that has become the gold standard for the removal of the gall bladder. Although there are many advantages to laparoscopy, the procedure may not be appropriate for some patients who have had previous upper abdominal surgery or who have some pre-existing medical conditions. A thorough medical evaluation by your personal physician, in consultation with a surgeon trained in laparoscopy, can determine if laparoscopic gallbladder removal is an appropriate procedure for you.

Most patients with symptomatic gallstones are candidates for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, if they are able to tolerate general anesthesia and have no serious cardiopulmonary diseases or other coexisting conditions that preclude operation. Some patients with very serious complications from gallbladder disease may not be eligible for laparoscopic gallbladder removal. In addition, patients in the third trimester of pregnancy should not usually undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy, because of risk of damage to the uterus during the procedure. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the first trimester of pregnancy remains controversial because of the unknown effects of carbon dioxide on the fetus.

Open cholecystectomy remains a safe and effective procedure for the treatment of patients who can tolerate general anesthesia but are not suitable for a laparoscopic procedure.

Are there any non-surgical treatment options for gallstones?

Oral bile acid therapy for dissolution of gallstones, with or without extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), provides a useful and safe, but ultimately less effective, alternative therapy for selected patients, especially those whose medical condition and/or personal preference precludes operative cholecystectomy. The drugs available for this are not only expensive, but need to be taken on a long-term basis and offer poor results.

What are the benefits of laparoscopic surgery?

Rather than a five to seven inch incision, the operation requires only four small openings in the abdomen.

Patients usually have minimal post-operative pain.

Patients usually experience faster recovery than open gallbladder surgery patients.

Most patients go home within one or two days and enjoy a quicker return to normal activities.

How does one prepare for laparoscopic gall bladder surgery?

The following includes typical events that may occur prior to laparoscopic surgery; however, since each patient and surgeon is unique, what will actually occur may be different.

Preoperative preparation includes blood tests, medical evaluation, chest x-ray and an ECG depending on your age and medical condition.

After your surgeon reviews with you the potential risks and benefits of the operation, you will need to provide written consent for surgery.

Your surgeon may request that you completely empty your colon and cleanse your intestines prior to surgery.

It is recommended that you shower the night before and the morning of the operation.

After midnight the night before the operation, you should not eat or drink anything except medications that your surgeon has told you are permissible to take with a sip of water on the morning of surgery.

Drugs such as aspirin, blood thinners and anti-inflammatory medications (arthritis medications) will need to be stopped temporarily for several days to a week prior to surgery. Please inform your surgeon if you are on any of these medications.

Quit smoking and arrange for any help you may need at home.

How is laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed?

Laparoscopic surgery uses a thin telescope-like instrument (laparoscope) which is inserted through a small incision at the umbilicus (belly button). The laparoscope is connected to a hi-definition video camera which projects a view of the operative site onto a high-resolution television monitor. The abdomen is inflated with carbon dioxide gas to allow your surgeon a better view of the operative area. Additional small incisions are made through which the surgeon inserts specialized surgical instruments. The surgeon uses these instruments to remove the gallbladder. Following the procedure, the small incisions are closed with sutures and covered with surgical tape. After a few months, they are barely visible.

Sometimes, it may be necessary to perform an X-ray, called a cholangiogram, to identify stones, which may be located in the bile channels, or to ensure that structures have been identified. If the surgeon finds one or more stones in the common bile duct(s), he may remove them with a special scope (choledochoscope), may choose to have them removed later through a second minimally invasive procedure (ERCP) or may convert to an open operation in order to remove all the stones during the operation.

In a small number of patients the laparoscopic method cannot be performed. Factors that may increase the possibility of choosing or converting to the "open" procedure may include obesity, a history of prior abdominal surgery causing dense scar tissue, inability to visualize organs or bleeding problems during the operation.

The decision to perform the open procedure is a judgment decision made by your surgeon either before or during the actual operation. When the surgeon feels that it is safest to convert the laparoscopic procedure to an open one, this is not a complication, but rather a sound surgical judgment. The decision to convert to an open procedure is strictly based on patient safety.

What is the recovery after gallbladder surgery?

Gallbladder removal is a major abdominal operation and a certain amount of postoperative pain occurs. Nausea and vomiting are not uncommon.

Once liquids or a diet is tolerated, patients leave the hospital 1-2 days following the laparoscopic gallbladder surgery.

Activity is dependent on how the patient feels. Walking is encouraged.

Patients will probably be able to return to normal activities within a week's time, including driving, walking up stairs, light lifting and working.

In general, recovery should be progressive, once the patient is at home.

The onset of fever, yellow skin or eyes, worsening abdominal pain, distention, persistent nausea or vomiting, or drainage from the incision are indications that a complication may have occurred. Your surgeon should be contacted in these instances.

Most patients who have a laparoscopic gallbladder removal go home from the hospital the day after surgery. Some may even go home the same day the operation is performed.

Most patients can return to work within 7 to 10 days following the laparoscopic procedure depending on the nature of your job. Patients with administrative or desk jobs usually return in a few days while those involved in manual labor or heavy lifting may require a bit more time. Patients undergoing the open procedure usually resume normal activities in four to six weeks.

Please make an appointment with your surgeon as per his instructions (usually within 7 days following your operation).

What complications can occur after gall bladder surgery?

While there are risks associated with any kind of operation, majority of patients experience few or no complications and quickly return to normal activities.

Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy are infrequent, but include bleeding, infection, pneumonia, blood clots, or heart problems. Unintended injury to adjacent structures such as the common bile duct or small bowel may occur and may require another surgical procedure to repair it. Bile leakage into the abdomen from the tubular channels leading from the liver to the intestine may rarely occur.

Numerous medical studies show that the complication rate for laparoscopic gallbladder surgery is comparable to the complication rate for open gallbladder surgery when performed by a properly trained surgeon.

When to call your doctor after gall bladder surgery?

Be sure to call your physician or surgeon if you develop any of the following:

- Persistent fever

- Bleeding

- Increasing abdominal swelling

- Pain that is not relieved by your medications

- Persistent nausea or vomiting

- Chills

- Persistent cough or shortness of breath

- Purulent drainage (pus) from any incision

- Redness surrounding any of your incisions that is worsening or getting bigger

- You are unable to eat or drink liquids